Living Data

Science Art & Talks

The experiential process of observation and reflection is key to art and science

and is an essential component in understanding interdependence

of all species and ecosystems, terrestrial and aquatic.

Paul Fletcher Animator

Science Art & Talks

Living Data Program for the 2013 Ultimo Science Festival, Sydney, September 12-21.

Pivot Drawing and Objects by Leanne Thompson

Many people view the world as a consumable resource. Art is made to break away from that perception,

to identify our selves as part of what we are destroying, at the pivot point of change for better or worse.

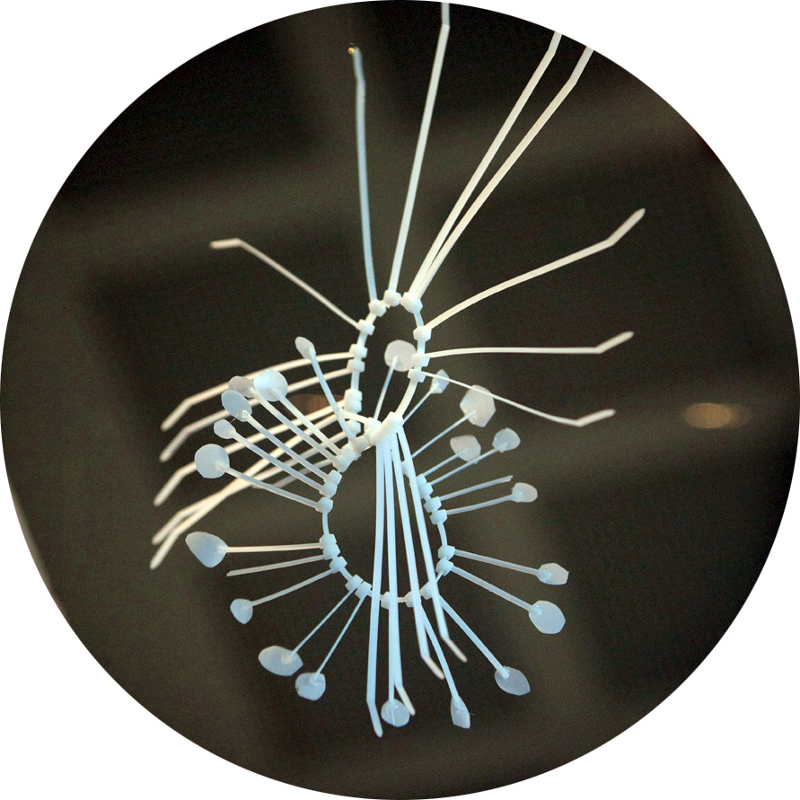

Leanne Thompson. Hitch hikers 2013. Phytoplankton forms in plastic

Leanne Thompson. Hitch hikers 2013. Phytoplankton forms in plastic

Leanne Thompson. (left to right) Pelagic 2012. Charcoal, acrylic, ink and gouache on rag paper. 2310 x 1080mm. Remote Foragers 2012. Paper, reclaimed plastic, lead, steel 4 elements each 1000 to 1700 x 600 x 400mm / total area approx. 1700 x 1300 x 1000mm (flexible)

Things that are outside of our field of vision don't enter our consciousness, especially not at the checkout.

Remote Foragers arose from dialogue with Dr Denise Hardesty from the CSIRO. She studies the Flesh-footed Shearwater, a magnificent pelagic bird, living on the open sea and returning to Lord Howe Island to breed. Her field work shows that more than 75 per cent of the birds they examine (via autopsy) have guts full of plastic. Other studies show this species as the most contaminated bird on the planet, this creature that lives in the remotest and supposedly 'cleanest' areas of the world. Dr Harnesty is reticent to make conclusions as to the dangers faced by this relatively common bird as there is a lack of historical data to compare with her findings. However, the obvious conclusion we can draw concerns the ubiquitous reach humanity. Contamination is found even in these remote locations. Things that are outside of our field of vision, they don't enter our consciousness - especially not at the checkout. The work plays with the notion of balance and extinction. Like toys or novelties they perch on their beaks alone. And though we may find the 'balancing act' amusing it highlights that their instinctual feeding habits are precariously disrupted by plastic detritus. The work on paper 'Pelagic' behind gives context to the environment and although appearing pristine these remote locations have concentrations of toxins within the food web.

Leanne Thompson

Just over ten years ago I discovered the work of Lyn Margulis, an evolutionary biologist with radical ideas ahead of her time, determined to take on the orthodoxy of science and convince them to embrace the truth she uncovered. She discovered that symbiotic mergers were the basis of evolution and that this created entire new paradigms for describing life from microscopic cells, through to a self-regulating planetary ecosystem and on to cultural narratives that define human interactions. These ideas resonated deeply with me, in my artwork and as a living being totally embedded in a complex and interdependent environment. I was excited to embrace 'working together' instead of in competition, in all facets of my life.

Like individual cells, we are capable of changing. We can change our perception, societal inertia and the impact of humanity on a macro scale. I believe that mindful, small actions by individuals have profoundly positive impacts and that these small movements, accumulated over hundreds of years of scientific enquiry, are gathering momentum as the urgency of climate change issues press in and we see the glimmer of understanding the entirety of the system. This explains the current interest in creativity, inter-disciplinary collaborations and dialogues, and in art as a perfect vehicle to make 'visible' our connections.

The artwork I make utilizes many materials and methods - printmedia, painting, work on paper, sculpture and installation. Many of the pieces are concerned with engaging the public, by shifting awareness through participation. I believe that creativity is a basic human trait and that the more people are encouraged to be creative, the quicker we will stop valuing a mass-produced lifestyle. My recent work aims to make visible the impacts of our lifestyle on the big picture.

I have been reading papers and approaching various scientists whose research covers areas I wish to understand. Initially, interest in marine debris and bio-accumulation took me on a journey through Cronulla Fisheries and Sydney Water. I discovered Dr Denise Hardesty at CSIRO and her research on the Shearwater population at Lord Howe Island. I came to know the work of Ghost Nets Australia and Kylie Higgins at DAFF, in relation to quarantine risks posed by exotic species floating on plastics in the ocean. From this I became aware of microscopic plastic contamination at the bottom of the food chain in phytoplankton, how this mutates and contaminates and then concentrates toxicity in all predators above. This biomass of microscopic life is diminishing, resulting in a reduction of oxygen released into the atmosphere. My current investigations have moved away from the oceans, inland to NSW Central Tablelands water catchments and land use and I am looking forward to working with Prof David Goldney, an ecologist from CSU about 'Landsmanship', our connection to elements we call resources and how we as a society allocate value to them and how to disengage development and growth from sustainability.

Notes for exhibition designers:

List of works (please refer to images above and below)

REMOTE FORAGERS, 2012 Paper, reclaimed plastic, lead, steel 4 elements each 1000 to 1700 x 600 x 400mm / total area approx. 1700 x 1300 x 1000mm (flexible)

PELAGIC, 2012 Charcoal, acrylic, ink and gouache on rag paper 2310 x 1080mm

These two works are installed together. "Pelagic" is pinned to the wall and the four stands with balancing birds (Remote Foragers) placed asymetrically in the area in front. There are a quantity of plastic feathers that can either lie scattered on the ground or "float" about 300mm above the ground (tba method to make support invisible) and mimic if they were floating on the water's surface. Any gusts of wind may dislodge birds.

HITCHHIKERS, 2013 Plastic cable ties suspended by fishing line. Sizes variable.

This work consists of 24 different elements ranging in size from 100 x 100mm to 400 x 400mm. The pieces are suspended from a matrix of fishing line at least 3250mm from the ground. This is to enable the phytoplankton to be hung at a variety of heights from 3100mm to 2200 and move gently on pivots on their line. The area covered is about 6m x 6m. Existing wall or ceiling brackets / rods / hookswill be used as anchor points.

SPINELESS, 2012 Recycled white plastic shopping bags, steel frame, paper 2900 x 1620 x 470mm

/Spineless /consists of a sculptural 'drawn' line in plastic formed into two screen-like surfaces. These are attached to the frame faces so they are taut. There is a third layer of paper inside and also attached to the frame. The height of the frame is supported and made safe by attaching to existing wall fixtures (vertical pipe).

Leanne Thompson. Hitch hikers 2013. Phytoplankton forms in plastic

Leanne Thompson. Spineless 2012.

To evaluate how reciprocity works in Living Data and how our program could be improved, I ask contributors,

What do you most value about our work?

What have you contributed?

How have you benefited?

How could our program be improved?

Leanne Thompson, Artist, Sydney

What do you most value about our work?

We invest care and energy into the things we value. The Living Data programme is a great example of this in two ways. Firstly, it shows to the public that there is a range of committed professionals working hard to research, disseminate and make sense culturally of the 'anthroposcene' era. Climate change is a key aspect to this age of the earth where human presence is having an overwhelming effect on current and future planetary systems and the environment.

Living data has also been a vehicle to bring individuals and academic peers in contact with each other in a new context. Whether artist or scientist, there is a movement to understand and share information across research disciplines. This need for interconnectedness is paramount if we are to envisage ways to change and overcome societal inertia.

What have you contributed?

I was excited to be able to exhibit sculpture and installation works from my PIVOT series - 'Spineless', 'Hitchhikers', 'Remote Foragers' and 'Pelagic'. All the works deal with human impact in a marine environment.

As an artist working in relative isolation in the studio, the Living Data programme allowed me to interact with artists and scientists, both within the exhibition and lecture context and through the internet and LD website. So this ability to contribute has also become an outcome as it has created new links and conversations with peers within the arts and more importantly – across the 'discipline divide'.

How have you benefited?

I have received quality feedback and support for my ideas and methodology. There are a couple of strong new links and many more potential contacts and collaborative projects that may result. Living data 2013 has opened new pathways for me to extend my current research.

I am hoping to be able to contribute again to this project and be part of its ongoing conversation.

How could the Living Data program be improved?

The programme had a very strong impetus from the science community – which was fantastic. This possibly limited the potential audience with many of the lecture participants being drawn from these academic faculties. There is an opportunity to widen this audience to the broader community through greater promotion within the art sector and general public.

Resources in the future could also be channelled into ways of dissemination of the science, through the art to the community.