Living Data

2017 Presentations

Disclaimers, Copyrights and Citations

Presentations/Index 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

5-7 July 2017

5-7 July 2017

Oceanic Bliss: From isolated heroes to interdisciplinary relationships

for the Depths and Surfaces Antarctic conference

Institute for Marine & Antarctic Studies, Hobart

Oceanic Bliss:

From isolated heroes to interdisciplinary relationships

20 min presentation

00:00

R:

It's well known that expeditions to Antarctica generate data that are vital for understanding climate change, and that these expeditions host artists to inspire care and protection of Antarctica.

Less well known is that many scientists are also artists, and that in times past their art has added depths of meaning to their data.

Today these expressions are kept separate from science.

00:26

G:

Subjective expressions have no place in current scientific literature where language strives to be as unambiguous as possible.

Here we speak as collaborators within a global movement of research, where individual expression is essential for understanding in relationships with people across disciples.

We acknowledge the creativity in science and in art.

00:43

R:

Our discussion emerges from three art-science explorations:

Firstly, the 2002 scientific expedition that took me to Antarctica as an artist with the Australian Antarctic Division.

Secondly, the Living Data program that I lead to make and present responses to our changing world, that are true to science, clear in language, appealing to the senses, evolving, and surprising (showing something new).

001:10

G:

Thirdly, the 2016 collaboration that we undertook with the Kur-ring-gai Ph Art+Science project led by Eramboo Artist Environment.

We define art as individual, subjective expression and science as collective, objective understanding. We agree that anyone can make art and that art does not necessarily speak for everyone, as opposed to science, where scientists must be trained in the scientific method and their work be peer reviewed, in order to contribute to consensus understanding.

We cite past and present investigations, including our own, to explain depths of meaning and experience that art can contribute to science, and the inspiration, awe and wonder that science can provide to art.

02:03

R:

Our focus is on art-science collaborations as in-depth and sustained interactions, and the changes in perception and behaviour that can occur through these.

02:13

G:

We believe this approach has special value for Antarctic research for its potential to generate new scientific knowledge, and to disrupt habitual thinking and feeling that is necessary to shift perception and behaviour.

02:27

R:

By 'Oceanic Bliss' we mean a primal feeling of connection that is heightened by scientific evidence of our selves as part of nature.

02:36

G:

The words of American writer Joseph Campbell, that "If you follow your bliss...the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living", resonate with both artists and scientists who feel compelled to do their work and could not imagine another way to spend their life.

02:52

R:

As artists we combine old and new technologies to discover and convey new knowledge: drawing, dance, music, song, digital imaging, motion capture, animation and interactive media.

We use languages that have evolved since pre-history to pass on stories that are vital to our survival.

00:11

The animation, 'Krill sex' (2010) is one such story.

G:

It's vital that we know about sex in the sea so we can protect the breeding grounds of marine species for future generations.

R:

It may surprise you to know that Antarctic krill are keystone creatures of the marine food web and that life in the ocean sustains life on land.

This animation makes sense of a chance observation of the entire mating dance of Euphausia superba (Antarctic krill).

As part of an Antarctic Marine Science voyage, a camera had been dropped to the sea floor to collect visual data of benthos (bottom-dwelling animals).

Krill biologist So Kawaguchi was surprised to see a swarm of krill in the video, and some unusual movement within it.

So invited me to trace the video frame-by-frame, and make the visual data readable.

Calling on my experience of drawing and dance, I imagined myself moving as the krill did in the water. As I drew and traced each video frame, I sensed the flowing pattern of the dance as a whole, and the most likely phases that we later identified as 'chase', 'probe', 'embrace', 'flex' and 'push'.

Over several weeks of conversation with So, reading scientific papers, and physically manipulating prawns from the local fish shop, I constructed the animation to represent what we all agreed was the most likely krill behaviour.

As I worked on this, my attention vacillated between sensing and thinking as I created and analysed the movement.

Combining feeling and thinking made the movement convincing for me and my hope was that other people would have the same reaction.

04:54

Happily, krill biologists and other scientists reported that they have experienced and witnessed double-takes in response to this work.

05:03

As artists we express beauty that we find in the natural world.

We also use illusions, metaphors, jokes and other devices to invite us to question our usual interpretation of things.

05:20

I made this drawing (with permission), of an Aboriginal engraving in Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park. The illusion of connection between mouth and genitals shocked me to attention. It made me think of our primal connection to the ocean for sustaining human life, and how Indigenous knowledge is lost, about how to manage and share resources.

05:43

The original drawing is on rock that's believed to be an ancient meeting place. It's likely to be part of a story-telling ceremony that would have involved dance, music and song. The lines would have been traced and re-traced over centuries.

05:55

Indigenous people recognise their traditional practices of resource management as their forms of science, and their arts as essential for passing on that knowledge.

06:03

G:

Science aims to understand nature and the rules that govern it. Ideas are tested through observations and experiments on a journey of creativity and discovery.

The scientist sees as an objective observer, adhering to a logical process of inquiry (the scientific method), and building upon a greater body of work. Inquiries that don't appear to be logical can lead to discoveries that are breakthroughs in understanding. These moments of new scientific insight can be, for scientists, as emotional and moving as our personal experiences of works of art.

06:38 The results of scientific observation and experimentation are communicated to the community of peers where they are scrutinised and further tested prior to their acceptance or rejection.

06:57 The work of a scientist continues with the communication of this new understanding to the wider, non-specialist community.

06:57

R:

In the Heroic era of Antarctic history, explorations were typically undertaken by people who practised as both artists and scientists.

The heroic era is distinguished by lack of mechanised travel and communication.

This may be why the arts played a key role in generating, expressing and communicating scientific knowledge.

07:29

Journals were commonly used for working things out, for noting observations and reflecting on experience. They typically include maps, plans, poetry and drawings.

07:41

G:

The lavish quality and scale of publications by botanist and cartographer, Jules

Dumont d'Urville (1790-1842) suggest a high regard for art in advancing science.

Antarctic drawings by Edward Wilson (1872-1912), surgeon, zoologist and artist with Scott's last expedition, serve as both art and scientific data.

Brian Roberts writes,

His watercolours were the first to convey an accurate idea of the beauty and subtlety of Antarctic colours... they will remain a permanent source of reliable information.

08:04

R:

As well as designing and making equipment for collecting specimens from the depths of the Southern Ocean, marine scientist Charles Harrisson drew and painted his experience. In this journal entry, repeated lines suggest movement of people through rock and ice, and the force of katabatic winds bearing down from the great ice plateau.

08:27

G:

In 1901 the geologist Louis Bernacchi (1876 – 1942) conveys in words his understanding and experience of Cape Adare, Antarctica.

This lack of snow is principally due to the very exposed position of the Cape to the south-east winds, and, perhaps, also to the steep and smooth nature of its sides, which afford no hold for any snowfall... [T]he peaks... tapered up one above the other like the tiers of an ampitheatre or those of the Great Pyramid of Cheops." (Bernacchi in Spufford. 2007. p.39)

Here, in one paragraph, objective and subjective languages combine to give different kinds of meaning to a single observation.

09:05

R:

Different responses to Antarctica are essential for attracting the different kinds of attention that people give to things.

09:14

In his drawings, marine biologist Alister Hardy (1896–1985) balances emotional connection and scientific accuracy. His art is also visual data for analysis.

09:25

Art and science can work together in education.

09:30

G:

Physicist Phillip Law (1912-2010) is widely known as an early leader in Australia's post-war Antarctic explorations, and the longest serving Director of the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD).

09:40

R:

Less well known is Law's enduring interaction with the arts, through personal experience in Antarctic culture, and his pioneering work to integrate science and art in education. Law supported sculptor Lenton Parr (1924–2003) in developing the Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) to integrate art, science and technology.

10:04

Their shared vision is expressed in the school’s emblem, designed by Parr as a form of Pentagram, a traditional symbol for the five senses. It refers to the various modes of perception and, to their aesthetic functions in the various arts.

10:19

Law’s wife Nel (1914–1990) was the first Australian woman to work in Antarctica.

She travelled with him to Mawson in the summer of 1960-1961.

10:30

Her 'Painting of an iceberg' suggests experience and understanding of physical and biological systems that interact to shape Antarctica. Birds sweep over water, air and ice, moving and moved within physical forces. Lines appear to be traced by hand, making it easy to imagine yourself drawing them, and to feel part of the picture evolving.

10:53

From her Antarctic experience and her ongoing interactions with scientists, Nel Law created a logo for the AAD (1947) that serves as an icon of connection.

11:04

Logos change to reflect changing structures and interests of organisations.

The current AAD logo is a generic Australian government crest.

11:15

G:

When and why did things change from the scientists also doing the art, to art-science collaborations?

11:23

R:

The change may relate to the advent of photography.

It may also relate to judgements by leaders of traditional Western culture.

11:31

G:

Since 1897 photography had been used as a means of communicating Antarctic explorations.

11:40

Then in 1911 two photographers demonstrated the new technology as an art form, as well as a means of mechanical representation:

Frank Hurley with Mawson's Australasian Antarctic Expedition and Herbert Ponting with Scott's last expedition.

11:55

Is this when the concepts of 'professional' scientist and artist were being born?

12:01

In the 2007 British Antarctic Survey's Art programme catalogue, the Introduction reads,

From expeditions without a professional visual artist we are often limited to the paintings of amateur artists, many entirely self-taught and usually painting and drawing for their own pleasure.

12:20

Since the start of Antarctic science, the arts have evolved within its research community, on voyages and on bases. Much of this material is ephemeral and difficult to document. If recognised, these expressions of shared experience and understanding may contribute significantly to bringing Antarctic science to a wider audience.

12:45

At this time of urgent need for everyone to understand, and to adapt to global climate change, more personal expressions from scientists are needed, so people can to relate the data to lived experience.

12:55

R:

In 1987 the Australian Antarctic Humanities program was born, with three Australian artists identified as professional and chosen to accompany a scientific expedition to Antarctica with the Australian Antarctic Division.

13:12

In the Foreword to the catalogue of their subsequent exhibition, Australian Minister Graham Richardson writes, "Twentieth-century Antarctica has essentially been the province of scientists".

13:21

No reference is made to the arts that emerge from Antarctic science communities.

What distinguishes Antarctic communities?

13:27

A sense of belonging to an international group of people who have worked there to learn how it works and is changing.

Strong relationships are formed are experience and knowledge are shared.

13:42

The AAD maintains a website that works for networking within and beyond the Antarctic community, including a database of Antarctic Arts Fellows.

13:50

The AAD Arts Fellowship program is one of several around the world that select and host artists in Antarctica. Other programs include Sur Polar (Argentina), and the British and American Antarctic Artist's and Writer's programmes.

14:04

Sur Polar artists have created and presented works in situ, with scientists and fellow artists involved in developing performances. Recordings of performances are presented around the world as video installations, with other art inspired by Antarctica and its science.

14:20

G:

The video, New Species, by Andrea Juan, attracts attention to scientific predictions of new species evolving in Antarctica with global warming.

14:30

Lorraine Beulieu's installation, 'Drapeaux', may startle you into seeing beneath the surface of Antarctic ice. The artist's naked body in embryonic form, is arranged to resemble Antarctic bedrock as it would appear without ice: vulnerable and unprotected.

14:48

R:

Sur Polar was the inspiration for Living Data, the program I began in 2012, to create and present responses to climate change.

14:58

Our increasing online interactions are leading to opportunities to present our work to new audiences.

G:

When we uploaded our video, Oceanic Bliss to Facebook, Andrea invited us to send it for a Sur Polar event she was staging in Madrid, of international responses to climate change inspired by Antarctic science.

15:18

R:

AAD Arts Fellows and Sur Polar artists have regularly featured in our program.

15:25

Sur Polar continues to foster the sense of belonging that exists within the Antarctic research community. However, its focus has shifted from Antarctica and its science, to Africa and its archaeological evidence of human origins.

Andrea’s current work is to create, facilitate and present art that celebrates humans as part of nature, through experience and understanding the place of our indigenous origins.

Indigenous ways of knowing are perhaps specially recognised by people who have worked in remote places like Antarctica. In both indigenous and Antarctic arts we find a clarity in language than reflects balance between art and science.

16:09

In Chris Drury's 'Explorers at the Edge of the Void', lines of text are written over lines of an actual echogram that was generated in Antarctica to ‘see’ through glacial ice.

The lines describe geological time. The written words evoke human presence: names of scientists and explorers whose collective knowledge builds an evolving big picture of human impacts on the natural world.

16:35

R:

Perhaps the first in-depth and sustained interactions between what we now call art and science, were experienced by our ancient forebears. For example, in the stories passed down about best fishing practices.

G:

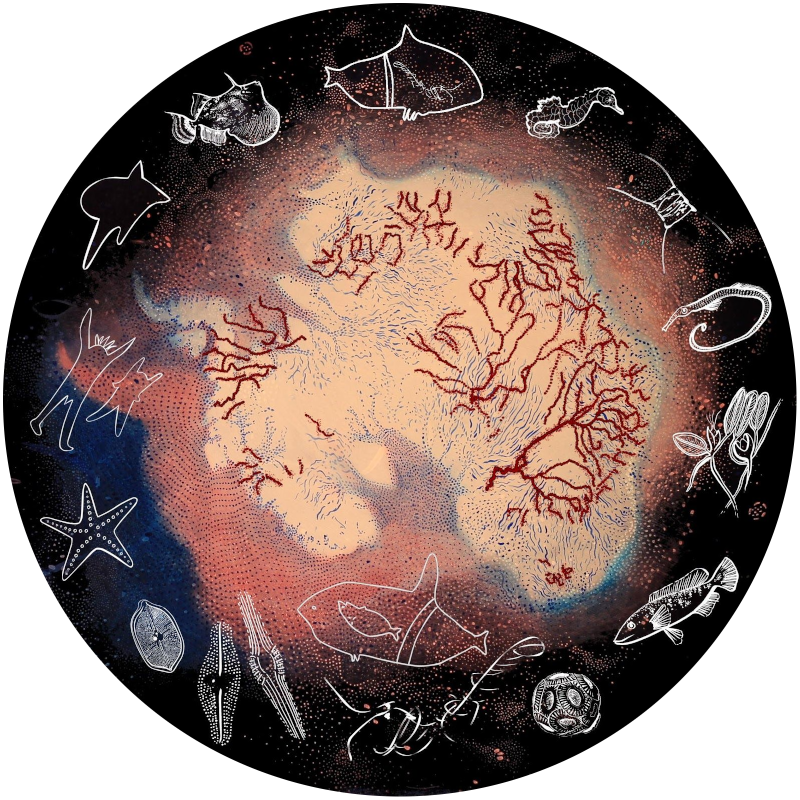

The painting, "Broulee catch", by Indigenous Australian artist Guindri, shows his continuing connection to the ocean, along the east Australian coast where whales still journey past his country as they travel to and from Antarctica.

This painting shows the relationship between seagrass, fishes and people. It could represent the whole Australian coast. It may also serve as another icon of connection, with its balance between what is known from experience and from science.

17:23

Perhaps recognition of multiple experiences of the same reality can bring us together to share strategies, for passing on what we believe is true, as far as we can tell at this point in time, with all the evidence that’s available.

17:40

R:

As the Age of the Anthropocene advances we see a shift towards collective, relational, interdisciplinary approaches to making sense of our place in the world.

17:50

In the field of climate art-science interactions the shift is happening through global networks like Living Data, that are mostly led by artists, with links to scientific, academic, commercial, and not-for-profit organisations.

18:05

Living Data interacts with other programs that include Cape Farewell, London, led by artist David Buckland; Lynchpin, Hobart, led by artist Sue Anderson; and Climarte, Melbourne, led by lawyer Guy Abrahams.

18:19

The chief scientist on the ship that took me to Antarctica (V7 2002) was Dr John Church, from the CSIRO. As we travelled he explained his research that would later result in these data.

It was John who convinced me that climate change was real, and it was more than his data that opened me up to accept the reality.

18:34

The moment we arrived at the Amery Ice Shelf, I witnessed his response to news relayed by satellite phone, that George Bush and John Howard had refused to ratify the Kyoto protocol.

That was the first time I had seen an emotional response from a climate scientist.

19:07

Data collected from above and beneath Antarctic sea ice are essential for identifying and monitoring shifts in the normal cycles of climate change caused by our massive burning of fossil fuels, and for understanding human impacts on the mating behaviours of marine creatures.

19:25

Our next steps?

Two projects:

One - Beware of pedestrians telling stories: expect evidence and artful seduction

Two - What happens under Antarctic sea ice at full moon?